The narrator of the story is Kurt Vonnegut, he doesn't call himself Kurt Vonnegut, but after listening to an interview with him, I can say with authority that the narrator is a man writing a story about a man writing a story about the WWII massacre at Dresden (very postmodern meta-fiction). The frame story is told in first person perspective and introduces us to the historical event that was the fire bombing of Dresden, Germany. The narrator/Vonnegut talks about how hard it has been to write a story about Dresden, "because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre." So what follows is Vonnegut's disjointed tale of Billy Pilgrim that doesn't feel disjointed at all, but rather a well composed and complete story that isn't told in chronological order. You have to be a really good writer to pull off this kind of story telling and make your reader feel like the story couldn't have been told any other way, despite the absurdity of it all.

Billy Pilgrim is the main character of the Dresden story, he's "tall and weak, and shaped like a bottle of Coca-Cola," and not bred for war. In the interview I listened to Vonnegut said that Billy Pilgrim was based on a real person that he served with in WWII by the name of Edward Crone. Edward Crone died in Germany from The Thousand Mile Stare. He was similar to Billy in that he wasn't meant to be a soldier. Crone's mind wasn't able to comprehend the absurdity of war, and so he disembarked from his body and sat in a stupefied stare, refusing to eat or drink until he died. This explains Billy Pilgrim, who is physically and psychologically unable to endure the horror of war and so invents an alternate reality in which he travels in time.

Billy Pilgrim believes he is abducted by aliens and taken to a planet called Tralfamador through a worm hole/time warp, and put on display in a zoo for the Tralfamadorians to observe. The aliens teach him about their concept of time and how every moment actually exists at once. The most important thing they emphasize to Billy is that any individual can choose to focus on moments of pure beauty.

Having been traumatized by war, Billy struggles to move past the ugliness of human existence as he moves through the story by time jumping to different parts of his life's timeline. His entire Tralfamadorian experience is a collection of different science fiction snippets from his favorite author Kilgore Trout. Billy began reading Trout's work when he was institutionalized for post traumatic stress disorder. Billy often jumps in time when he is experiencing some kind of memory associated with the war. His psychological disassociation seems characteristic of a man whose soul is dislodged by the experience of war, and yet his invention of the alien abduction and subsequent insights about the truth of existence is the means by which he overcomes the pull of The Thousand Mile Stare.

The most interesting thing about Billy is that he isn't interesting at all. Billy isn't a hero, but rather a passive character who is pushed and shoved along in life without ever really making decisions. Vonnegut acknowledges this when he says, "There are almost no characters in this story and no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces." What Vonnegut is able to achieve is the portrait of a man who was drafted, thrust into war, captured, starved, ridiculed, forced into labor, forced to lay witness to the bombing of Dresden and then made to dig up bodies from the rubble that resembles the pock marked desolation of the moon. And all of that is while he's around 18-years-old.

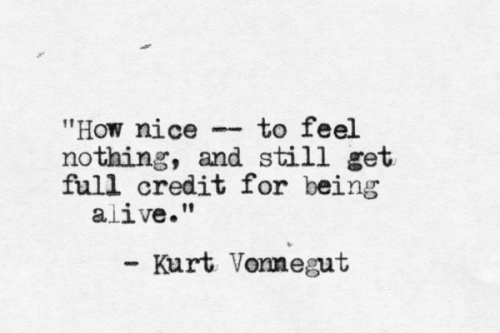

How does a youth survive an experience like that? As an adult Billy follows the societal expectations of marriage devoid of any real love from Billy because he doesn't feel things, a dull life in optometry always characterized by the sameness of all the optometrists and their wives, children that he sires but doesn't really know, an alien abduction that may or may not have actually happened, a drunken affair that felt like a mid-life obligation, and the survival of a plane crash that triggers a reaction akin to The Thousand Mile Stare, and then he's assassinated by a man he knew from the war. So it goes. Billy's life is Vonnegut's satirical commentary about these "enormous forces" that rule our lives. If we don't become active participants in our lives then these greater forces end up controlling and molding our lives.

I don't really have any criticism about the story. I enjoyed every part of it despite the underlying war commentary that really got to me at the end. What war does to the individual and to whole cities of innocent people disconnected from the main military conflict is tragic. I didn't know about the bombing of Dresden and how it was a British idea that Americans carried out as a test to facilitate the end of a dragging war. Dresden was the precursor to Hiroshima.

Vonnegut's writing is smart and I can see how some would think Slaughterhouse-Five is too contrived. I think I would have had a similar reaction had I not loved the writing as much as I did. Vonnegut's choice of images and details brings the story to a visceral level. The tone he is able to achieve is one of dark humor and surprising aloofness that never becomes preachy. Vonnegut's choice in telling Billy Pilgrim's story the way he did structurally allowed him to achieve a cultural and war commentary without being verbose. I marvel at his genius.

Having been traumatized by war, Billy struggles to move past the ugliness of human existence as he moves through the story by time jumping to different parts of his life's timeline. His entire Tralfamadorian experience is a collection of different science fiction snippets from his favorite author Kilgore Trout. Billy began reading Trout's work when he was institutionalized for post traumatic stress disorder. Billy often jumps in time when he is experiencing some kind of memory associated with the war. His psychological disassociation seems characteristic of a man whose soul is dislodged by the experience of war, and yet his invention of the alien abduction and subsequent insights about the truth of existence is the means by which he overcomes the pull of The Thousand Mile Stare.

The most interesting thing about Billy is that he isn't interesting at all. Billy isn't a hero, but rather a passive character who is pushed and shoved along in life without ever really making decisions. Vonnegut acknowledges this when he says, "There are almost no characters in this story and no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces." What Vonnegut is able to achieve is the portrait of a man who was drafted, thrust into war, captured, starved, ridiculed, forced into labor, forced to lay witness to the bombing of Dresden and then made to dig up bodies from the rubble that resembles the pock marked desolation of the moon. And all of that is while he's around 18-years-old.

How does a youth survive an experience like that? As an adult Billy follows the societal expectations of marriage devoid of any real love from Billy because he doesn't feel things, a dull life in optometry always characterized by the sameness of all the optometrists and their wives, children that he sires but doesn't really know, an alien abduction that may or may not have actually happened, a drunken affair that felt like a mid-life obligation, and the survival of a plane crash that triggers a reaction akin to The Thousand Mile Stare, and then he's assassinated by a man he knew from the war. So it goes. Billy's life is Vonnegut's satirical commentary about these "enormous forces" that rule our lives. If we don't become active participants in our lives then these greater forces end up controlling and molding our lives.

I don't really have any criticism about the story. I enjoyed every part of it despite the underlying war commentary that really got to me at the end. What war does to the individual and to whole cities of innocent people disconnected from the main military conflict is tragic. I didn't know about the bombing of Dresden and how it was a British idea that Americans carried out as a test to facilitate the end of a dragging war. Dresden was the precursor to Hiroshima.

Vonnegut's writing is smart and I can see how some would think Slaughterhouse-Five is too contrived. I think I would have had a similar reaction had I not loved the writing as much as I did. Vonnegut's choice of images and details brings the story to a visceral level. The tone he is able to achieve is one of dark humor and surprising aloofness that never becomes preachy. Vonnegut's choice in telling Billy Pilgrim's story the way he did structurally allowed him to achieve a cultural and war commentary without being verbose. I marvel at his genius.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete